- Home

- Lucien Gregoire

Murder in the Vatican Page 15

Murder in the Vatican Read online

Page 15

Nevertheless, despite Montini’s and Pius’ denials in the press the rumor Montini refused the red hat persists even today.3 Yet, what we know of him tells us he did not refuse the red hat.

Most cardinals—though they may pretend otherwise—yearn to succeed to the papacy. Men are not, as one might be led to believe, dragged yelping, howling and squealing against their will to the papal balcony. This was particularly true of Montini and Wojtyla who openly voiced their papal ambitions throughout their ministries.

Yet, unlike Wojtyla, it was expected Montini would succeed to the papacy. Unlike his colleagues Roncalli and Luciani who feigned humility in accepting the post, Montini accepted it as his legacy.

In 1954, Pius moved Montini from the Vatican to Milan to lessen his grasp on the Curia votes. Again, he withheld the red cap.

Pius’ intent was obviously to exclude Montini from the conclave which would diminish his chances. Yet, when Pius died, Montini still controlled a block of cardinals; they would vote only for him or his choice. This is seen in newspapers which listed Siri and Montini in a dead heat for the papacy as the conclave opened on October 25, 1958 despite Montini was not a cardinal. In retrospect, neither Siri nor Montini won the election. How could this have come about?

The leading candidates in the election were Montini followed by Roncalli on the liberal side of the aisle and Siri unchallenged on the conservative side. The war had been a wake-up call as to the dangers of frozen conservatism. The trend was away from fascism.

A liberal at that time was not what a liberal is today. Both the liberal and the conservative had convictions concerning doctrine. The liberal, however, had an open-mind in considering modifying doctrine in those cases where it unfairly penalized the lives of innocent people. The conservative, on the other hand, was fixed in his convictions, he didn’t care how much suffering doctrine imposed upon innocent people. At the time, a conservative was a dedicated fascist limited only to what had been lost to him by Hitler in the war.

In retrospect today, one can only surmise Pius’ strategy—faced by a growing open-minded majority—was to split the liberal vote between Roncalli and Montini and pave the way for his favorite son—the youthful conservative archbishop of Genoa, Giuseppe Siri.

In that Roncalli won the election, it follows Montini yielded his votes to the aging cardinal. What’s more, we know he did this before the conclave went into session as Montini was not in the conclave. How do we know this? Post-election events clearly tell us this.

Shortly after his election, on December 15, 1958, John XXIII elevated Montini and twenty-two of Montini’s loyal supporters to the College of Cardinals. Should John have died the following day, Montini would have won a successive election in a landslide.4

John’s intention is seen clearly in the consistory listing: Montini is listed first. Never before in the history of the Church or since, has a pope held a consistory so soon after his election. John’s intent was to guarantee Montini succession should anything happen to him in the short term. It is obvious to all but the most gullible, a deal had been struck between the aging Roncalli and the youthful Montini in the days leading up to the 1958 conclave.

The practice of listing their choice of succession first has been true of many popes. Albino Luciani led the list of thirty cardinals in Paul’s consistory of March 5, 1973.

John did something else quite unusual. On the same day he made Montini a cardinal, John made both his and Montini’s favorite son, Albino Luciani, a bishop.5 One can only surmise this was to position Luciani to succeed Paul should Montini fall victim to foul play.

When Roncalli became archbishop of Venice he had adopted the young priest from Belluno as an aide. The bond between Montini and Luciani dated back much further. During the war, Luciani had intervened many times on behalf of the oppressed and often enlisted Montini’s weight with Pius to bring about compassionate decisions.

History confirms a deal had been struck between Roncalli and Montini before the conclave began. What’s more, those cardinals Montini had persuaded to vote for Roncalli in 1958 knew they were actually voting to place Montini in direct succession to the throne.

Setting this aside, there is the possibility strategy, politicking and collaborating among men has nothing to do with electing a pope. It may be Christ did speak to those cardinals committed to Montini in the conclave and told them to vote for Roncalli.

Although the choice of Pius remains vague, and the choice of John could not be more clear, there was no case more certain than was Paul’s intent Albino Luciani succeed him.

Shoes of a Fisherman

Of all the demands Albino Luciani had made upon the Vatican through the years, none was more widely publicized than was his ongoing demand it liquidate its treasures to annihilate poverty and starvation. In his early years, he didn’t have to look further than his own village to see poverty and starvation.

In the sixties, as a bishop, he saw much more. He became a close friend of Pericle Felici when the latter was serving as papal nuncio to Africa. Through Felici’s intercession, he established a mission at Burundi, manning it with his own priests and monks.

When he first arrived in Vittorio Veneto and pressured his priests to sell their gold he gained worldwide attention. In the coming years, in an ongoing assault, Luciani brought public pressure on Rome to sell treasures held in warehouses and not on display to help finance his African venture, but to no avail. Nevertheless, of all the things Luciani had gained notice for, none had gained more press than his ongoing condemnation of the hypocrisy of the Vatican treasures.

In 1968, the Anthony Quinn movie Shoes of the Fisherman premiered. The film depicted the rise of a Russian to the papacy who resembled the real life Luciani to a tee. It told of a bishop who strolled in shorts and sandals incognito through the darkened ghettos of his diocese under assumed names and, most striking of all, it exploited Luciani’s most widely known threat to Rome—liquidation of the Vatican treasures to annihilate poverty in the world.

In the film, Anthony Quinn, a newly appointed pontiff, shocks the world by announcing his intent to sell off the Vatican treasures to annihilate poverty and starvation in communist China.

That the leading character in the film so closely resembled Luciani and ignored, for the most part, the character Morris West had built into his 1963 novel brought the bishop of the Veneto country much notoriety. There is no mention at all of the liquidation of Vatican treasures in the book which is the focal point of the film. Regardless, the movie was a godsend for Luciani and the fame it brought him financed many of his third world ventures.

In the following year, 1969, Paul VI raised Luciani to Archbishop of Venice. The Pope sent a public message to the bishop of the remote mountain province. “The time has come for you to begin your journey to Rome, for the gods of Hollywood have spoken!”6

Everyone knew exactly what Paul was talking about.

The papal buzzer

Whenever, cardinals gathered in Rome and Luciani was among them, though only a common bishop, he sat next to Paul. In one well publicized instance at a public audience, Paul could not locate the little buzzer on his chair that would summon an attendant.

Luciani reached for Paul’s hand and guided it to the button. Paul looked at him. Not aware the microphone would pick up his comment, said, “So, you already know where the papal buzzer is.”7

The papal stole

In 1967, at Christmas service in Vittorio Veneto, Paul removed his stole and placed it upon Albino Luciani’s shoulders. Through the years, Paul had often repeated this gesture. Yet, it usually went unnoticed until he did it in 1972 in the Piazza San Marco in Venice before twenty thousand people and an international television audience. Now the whole world knew Luciani was the choice.8

Stacking the College

In the early 1970s, Paul began stacking the College of Cardinals to the left. He raised the number of voting cardinals from eighty to one hundred twenty and filled most of the vacancies with liberals

.

In the consistory of 1973, Paul not only made Luciani a cardinal and listed him first, but of the other twenty-nine appointed that day, there was not one who would not vote for Luciani.

As a follow-up to having raised the voting cardinals to one hundred twenty, he raised the authorized number of cardinals to one hundred thirty-eight in order to hold the voting conclave at one hundred twenty. This created eighteen additional voting vacancies, most of which had, in rapid consecutive order, been filled by Paul with liberals before his death. Of the last fifty-six cardinals Paul appointed, all but three were known to have liberal tendencies.

The voting conclave had remained at seventy for five hundred years. John XXIII, when elected, in order to guarantee his successor would be Montini, raised the number to eighty and made it clear he would not be restricted to it—when he died there were eighty-seven.

A cardinal has only two responsibilities—he elects a pope and advises a pope. Yet, popes have many closer advisers than cardinals from heads of state to common laymen, priests and nuns. It makes no difference whether he has fifty or a thousand cardinals. The only unique function of a cardinal is his role in electing a pope.

Paul’s only possible motive in increasing the number of voting cardinals was the same as that of John. To guarantee his favorite son from Venice succeed him, he had only two choices: 1) he could refuse to reconfirm existing conservatives when their terms lapsed, or 2) increase the authorized number of cardinals and fill the vacancies with liberals. Something we know, in retrospect, he did.

Paul also eliminated cardinals over eighty from voting—at the time all eighteen over eighty were ultraconservatives who otherwise would have voted against Luciani. Had Paul not made this particular change, his successor would not have been Albino Luciani.

As he lay on his death bed, Paul could be reasonably confident through the process of addition that Luciani had about seventy-five votes; a marginal win—the two-thirds plus one vote required. Yet, he could not be certain his choice would succeed him.

Barely conscious, falling in and out of a coma, the night before he died, Paul promoted Cardinal Yu Pin of Taiwan, to the position of Grand Chancellor of Eastern Affairs—the most powerful position in the Eastern Hemisphere. His intent was to give Yu Pin the influence in the upcoming conclave to add the dozen or so eastern cardinals to Luciani’s list. When Paul went to rest, he knew Albino Luciani, the brave young priest he had once saved from excommunication, would succeed him. That is, if nothing happened to Yu Pin.

The Opus Dei candidate

In that all modern popes have succeeded to the papacy through the influence of their predecessors, one might wonder how Karol Wojtyla, unknown in the media, wiggled his way into the papacy.

Being the conservative he was, Karol knew he would never get the nod from Paul. We know him as the most widely traveled pope in history. He was also the most widely traveled cardinal.

In the ten years he was a cardinal, Karol visited more than two hundred cities. He visited almost every field cardinal, including his well publicized six-week trips to the United States in 1969 and 1977 in which he visited every city where a cardinal was in residence.

There is no record these trips had to do with fund raising. One might ask, what reason could he have had to have spent so much money from the poor box for so many expensive vacations? What could these trips have to do with his responsibilities as archbishop of Krakow? The only logical answer is he was lining up the votes.

In the 1978 conclaves, Wojtyla was the only member who had a personal relationship with each of the others. He had slept in each of their mansions, had tasted wine with each of them at dinner and enjoyed morning breakfast with each of them on their verandahs.

In truth, Karol did not rob the poor box to pay for his trips.

Like Albino Luciani, Karol Wojtyla had a benefactor who would pave his way to the top. The Polish cardinal’s ten year ‘campaign’ was funded by his good friend Josemaria Escriva, founder of Opus Dei. Wojtyla and Escriva had met in 1965 at the Vatican II Council in Rome. The following year Karol made his first ‘campaign’ trip.

Opus Dei is a commune; it requires members to contribute most of their income to the cult. Though a secret society, it is no secret it uses its resources for political purposes and it is no secret, today, it financed the Polish cardinal to the pinnacle of the Catholic world.

Opus Dei is an order of extremists. It believes salvation can be obtained only through adoration. It does not believe helping others has anything to do with it. Although Opus Dei is per capita one of the richest organizations in the world, it does little to help others.

Its sole brush with charity is its Harambee mission in Africa which it uses as a pretext to indoctrinate youth into its fascist fold.9

It was founded in 1928 when movements within and outside the Church started to move Catholicism toward the left.

Women gained the right to vote and were threatening to leave the kitchen. Jews were permitted to practice their religion in Catholic countries. Homosexuality was gaining a level of tolerance.

On the world stage, the Soviet Union, the great enemy of fascism, was coming to power. In his own country of Spain, democracy was raising its ugly brow. All these things horrified Escriva.

Escriva’s thesis, The Way, dictates the path to salvation: “Blessed be pain. Loved be pain. Sanctified be pain. Glorified be pain.” It so closely mirrored Mein Kampf he was accused of plagiarism.10

In the late thirties, Licio Gelli, an officer in Mussolini’s black shirts who had once served as an intelligence officer under Hitler, was sent to Spain to support Franco’s insurrection of the Spanish people. Escriva and Gelli quickly struck up an enduring relationship.

Escriva and Gelli were at his side when Franco came to power in 1939. Opus Dei quickly infiltrated Franco’s cabinet and brought about ruthless oppression of the Spanish people—the clandestine cult providing the ideology and Franco providing the executioners. Together they murdered over a million innocent people.

In March 1941, Escriva praised their great ally, “Hitler will take care of the Jews. Hitler will take care of the Slavs.”11 After the war, he would minimize the damage. Escriva told a reporter, “History is unfair to Hitler. It claims he murdered more than six million in his camps, whereas, less than four million actually died.”12

Gelli’s rat line funneled Nazis to South America. Although Gelli usually gets the historical credit because he headed it up, the rat line was in reality an Opus Dei scheme of which Gelli was a member.

In 1946, Escriva and Gelli enlisted Carlos Fuldner into the ranks of Opus Dei. Fuldner had been an officer in Hitler’s SS Guard and an old friend of Escriva, probably why Escriva was able to make his remark in 1941 ‘Hitler will take care of the Jews…” as only the SS Guard knew what was going on in the death camps at that time.

Gelli and Fuldner ran rescue efforts from Madrid to Argentina for Nazi war criminals seeking refuge. Among those rescued were Adolph Eichmann and Josef Mengele though there are conflicting reports the latter may have escaped through the Pius XII rat line—a network of monasteries from Poland through in Italy to Naples.13

Knowing he controlled many votes, Alvaro Portillo, primate of Opus Dei, invited Luciani to address its convention. In his invitation, he cited the commonality of Luciani and Escriva—Imitation of Christ. The strategy was to win Luciani’s support for Wojtyla.

Luciani refused, “True. Msgr. Escriva and I are in common. We both believe the Imitation of Christ is the path to holiness. Yet, Escriva’s teachings are materialistic. He believes salvation can be had solely through the Imitation of Christ’s death, self-flagellation and the chanting of vain repetitions. I believe salvation can only be had through the Imitation of Christ’s life, in helping others…”14

When Opus Dei met in Milan the next month Portillo introduced its candidate as “Papa Stanislao.” The crowd broke into a frenzy for forty minutes before Wojtyla was able to begin his speech. Stanislao was Karo

l’s chosen name should he ever rise to the top.15

When Karol Wojtyla rose to the papacy, like Franco before him, his cabinet was infiltrated by Opus Dei members from Agostino Casaroli at the top down to his valet Angelo Gugel at the bottom.

His personal secretary, Stanislaw Dziwisz, was a flagellation practitioner of the cult as if to hint His Holiness, himself, required an occasional flogging of the rump while he prayed the rosary.

When, in 1982, John Paul II raised Opus Dei to Prelature of the Holy See, he did it in the face of an uproar, not only among Jews, Slavs, homosexuals and others Escriva had persecuted through the years, but among men and women of good conscience all over the world. Twenty years later, when he canonized Escriva a saint, it confirmed to all—except the most gullible—a tit-for-tat deal had been made between Josemaria Escriva and Karol Wojtyla in 1965.

Conclave rules

Unlike what one might think, popes are not elected in conclaves. Consider the rules as they apply before, during and after a conclave.

If a cardinal discusses anything relative to an election before, during or after a conclave, he automatically self-excommunicates himself. No cardinal has ever revealed anything that pertains to an election whether it occurred before, during or after a conclave.

Yes, after a cardinal dies, an author might claim the cardinal had confided with him before his death and write a book to capitalize on the suckers. Yet, no media has ever published what a cardinal might have said out of conclave while he was still alive.

In the two weeks between a pope’s funeral and the ensuing conclave, the cardinals are sequestered together in Rome.

Unlike what the public might believe, this time is not spent in prayer. It is spent electing the next pope. Cardinals can often be spotted in the red cap-frequented haunts in the city chatting away.

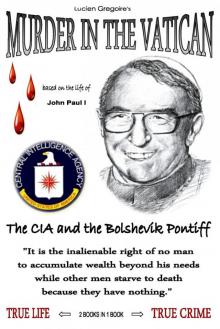

Murder in the Vatican

Murder in the Vatican